Winkling out budget data in Israel

In Israel, what started as an attempt to find out how much the government spent on firefighting became a much larger project, as it slowly emerged that published budget data was unintelligible, late, and – as gradually became clear – wrong. A group of coders and activists used official requests, lobbying, campaigning, and legal action to get fuller, better and and more up-to-date figures. With some heavy data processing – and some crowd-sourcing – they cleaned this data and present it in a visual form, and as time went on, interactive features were added to enable citizens to explore the data in detail. As a result, proposed budgets became a significant element in the national political debate.

Fire on the mountain

On 2 December 2010, a deadly forest fire engulfed Mount Carmel in Israel and raged for four days before finally being brought under control. The fire services claimed that their capacity to respond effectively had been impaired by chronic underfunding, and that despite the Mount Carmel disaster, their budget was not being increased in the proposed budget for the following year, 2011–12. The government denied this, but the budget data was not public and it was difficult for the public to know what to believe.

Amid claim and counterclaim, a developer, Adam Kariv, set out to find the truth, along with other members of The Public Knowledge Workshop (Hasadna). Over the following few years, they overcame a series of obstacles to bring previously shadowy Israeli budget data into the open.

Activism and hacktivism

The annual Israeli government budget is drafted by the Ministry of Finance (MoF). Hasadna found that data for previous years was published on the MoF’s website, but it was in a chaotic collection of data formats and file types, which could not be interpreted without expert help. For the proposed budget for 2011–12, they could find no data at all.

Using expert programming skills and with the help of an economist, the group were able to process the existing data and load it in a consistent form into a single database. Building on this, they created a website presenting visualisations of the past budgets. Initially, with government permission, this appeared as an official government website, though it was later taken out of the .gov.il domain and presented as a separate site.

Meantime, to get the proposed 2011–12 budget, they approached Michael Eitan, a minister responsible for the new government data office. Eitan was supportive and, by making an official request, was able to get the proposed budget from the MoF. It was therefore possible to present usable visualisations of both forthcoming and past budget data.

Hasadna continued to work on the site, adding features to drill down into the budget in more detail and to compare budgets in different years. However, they soon discovered a problem. A visualisation is only as good as the data is is based on, and the data they had been given was incomplete and, in fact, highly misleading.

The Public Knowledge Workshop in action (Credit: The Public Knowledge Workshop)

Shifting budgets

The published data which Hasadna had worked with related to the budget as it is proposed by the MoF at the beginning of each financial year and amended or accepted by the Finance Committee, a committee consisting of 25 members of the Knesset or parliament (MKs). However, during the course of the year, the MoF propose numerous amendments to the ongoing budget, effectively transferring money from one area to another. These amendments change on average 13% of the original budget. Like the original budget itself, these transfers were presented to the MKs in reams of complex documents and tables, with little notice before a decision was needed, so it was not clear that there was sufficient democratic oversight of the true amounts budgeted to different areas.

When this problem came to light, Hasadna set out to discover how the budget had changed over the 2010–11 budget year. Eitan again approached the Ministry of Finance for the transfer data. The Ministry claimed, strangely, not to have the data in spreadsheets. Instead they produced the paperwork from all Finance Committee meetings over the year. This could not be used without a huge amount of work to digitise and combine all the data.

Nothing daunted, Hasadna created a crowd-sourcing platform enabling volunteers from the Israeli open data community to work on the digitisation task together. Meantime, the coders added features to the budget site to show how the transfers had changed the budget during the year. On the day the new version was due to launch, the MoF, fearing negative publicity from the affair, finally ‘found’ the electronic version of the transfer data, and agreed to provide it for past years.

Looking ahead

One vital piece of the jigsaw was still missing. The data on transfers was only available for past years. Hasadna and others felt that proposed transfers should be published at the time they were proposed, so that there could be a public debate about the merits of the budget changes before they were approved. This would also help the MKs on the Finance Committee to make more informed decisions. The ministry, however, would not agree to provide the data in advance.

Matters were put on hold by a general election campaign in 2013. After the election, Michael Eitan had lost his Knesset seat, and the ministry he had held was abolished. Hasadna therefore approached a new MK, Stav Shaffir, at 27 the youngest ever. Shaffir, who had been one of the leaders of the 2011 social movement protests in Israel, had decided to change the system from within – and stood for election. On gaining a seat in the Knesset she was chosen to serve on the Finance Committee, so she was ideally placed to help.

Shaffir fought for publication of the transfers, even asking for Committee votes on the transfers to be suspended until they could be published. After a month of wrangling, the Ministry agreed to publish them, but once again they provided only scanned documents. Shaffir, unsatisfied, asked for the data to be provided in electronic form, but in vain. She also filed a case in the Supreme Court, claiming that the transfers broke the Ministry’s rules and amounted to misconduct. (The transparency issue was mentioned in the case, though it was not the subject of the alleged misconduct.) Shaffir also organised a public conference at the Knesset on budget transparency, which got a fair amount of media coverage.

Visualising change

Finally, in March 2014, with the appointment of a new head to the MoF’s Budget Division, the ministry decided not to wait for a Supreme Court judgement. They announced that the budget transactions would be published in advance on the ministry’s website from the next sitting of parliament.

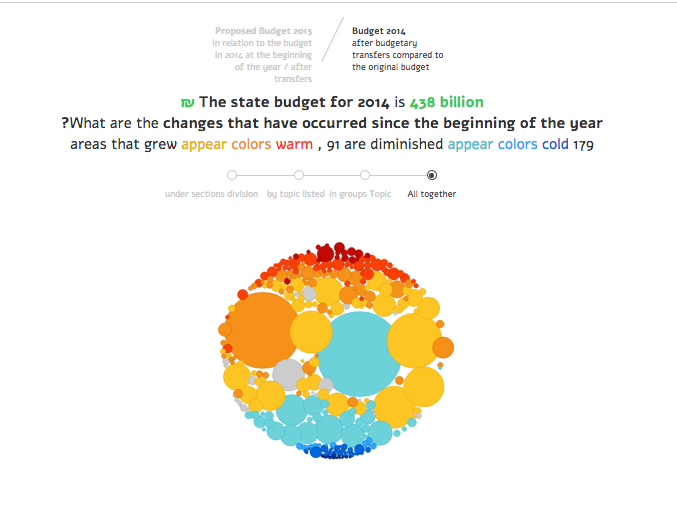

The latest version of Hasadna’s budget tool, called ‘Budget Key’, was launched in December 2014. The transfer data is now a central feature: animated bubbles let the viewer see which budgets grew and which were reduced through the year. The tool automatically polls the MoF site for new and proposed transfers and users can request e-mail alerts when these are published.

The Budget Key homepage screenshot

The Budget Key homepage screenshot

Down the rabbit hole

Mushon Zer-Aviv is a web designer who has been involved in the project from its early days. In an article charting on the history of the site, he reflects that it reveals a ‘transparency paradox’: as he puts it on the The transparency & accountability blog,

‘The more you make accessible, the deeper the rabbit hole goes.’

The more data is available, the more people can see how much more is still being withheld - and the louder the demands for even fuller publication of government data. Hasadna’s work on budget data is by no means finished, as they seek to open up information on government contracts, local government finances, and more. Rather, it is simply another part of the ongoing awakening in Israel to the possibilities of open government data.

- Uredi stranicu Uredite stranicu Pomoć i upute